- 2017 STEPHANIE BUHMANN in conversation with Bettina Blohm

- 2016 Fermaten und Oszillationen

Ein Gespräch zwischen DONNA HARKAVY und Bettina Blohm - 2004 Screen of Emotion, Landscape of the Mind

DIANE THODOS in conversation with Bettina Blohm

BETTINA BLOHM with Stephanie Buhmann

Neukölln, Berlin

February, 2017

Stephanie Buhmann: You work in New York and Berlin, traveling regularly back and forth. However, each of your studios is dedicated to a different purpose.

Bettina Blohm: When I first set up my studio in Berlin in 2008, I immediately thought that I wanted to have a different kind of studio than in New York, where I'm focused on painting and have lots of daylight. My studio in Berlin is smaller in comparison and I only work on paper here. This allows me to concentrate on either drawing or painting for longer stretches of time.

SB: Do your works in both mediums still intersect or do you view them as somewhat separate, self-contained entities?

BB: Both the works and thoughts intersect. In New York, I still make small sketches for paintings, for example, to note compositional ideas. As the painting progresses, I keep continuing to sketch. However, in Berlin I focus on independent drawing series. It’s my time to think, develop new ideas, play around a bit, and essentially, to open up. This back and forth between working in two different media and traveling between two different cultures with very different aesthetic predilections has been very good for my work.

SB: Your most recent works on paper completed in Berlin hint at geometry, albeit rendered with a free hand rather than precise tools. There is an overall rhythm rooted in squares, verticals and horizontals. From where do you source your compositional elements and how do you bring them together?

BB: Originally, most of my ideas came from the landscape. In fact, I’ve been doing landscape drawings for about twenty-five years. So I think a lot of my sense of rhythm stems from there. Meanwhile, I use the grid as a basic structure, against which I set different ideas, be it the combination of two grids or particular shapes, for example.

SB: Many of your works ponder such a particular shape, as you call it, in different variations. The results evoke themes of repetition, reflection and transition.

BB: In general, I’m interested in opposites. I often set up two different systems or two ideas that guide the composition in both my painting and drawing. Sometimes it’s the same idea, but explored in two different scales. These parameters function like rules, against which I then like to push.

SB: Do the same set of rules describe the core of an entire group of works that then functions as a series?

BB: Yes. I usually will get excited about a certain idea and I will subsequently play around with it, trying to develop different versions of it.

SB: When looking at your most recent group of works on paper, one can trace a particular structure. Each drawing is characterized by the interplay of square and rectangular shapes on a plane.

BB: All of these works are in a vertical format, which is something I haven’t really used for a long time. The vertical format always suggests the figure in some ways, whereas a horizontal format evokes a landscape. I call them Mosaikformen [Transitional Forms], which in evolutionary biology define organisms that have characteristics of two different groups of organisms. So let’s say birds and crocodiles originally had the same ancestor and that ancestor would have characteristics of both species. These new drawings are based on two systems. First, there is a grid made by four sections in height and three sections in width. I then divide that grid further using a smaller scale. However, I don’t draw the grid from top to bottom and left to right. Instead, I draw it in segments so that each segment of the grid begins to move against another. This process is evocative of handwriting and it invites irregularities. These two grids of different scale seem to lean on each other.

SB: It’s interesting that these grids seem to be in flux, which is a quality that’s usually not associated with these structures. In your work, they almost appear organic and less rooted in notions of predictability and stability.

BB: That’s a very good point. It’s kind of quirky and personal. If you think of a city grid, you associate it with a rigid infrastructure. I use it in the opposite way, as something that you can manipulate and that is alive. In addition, I may introduce a curvilinear line that weaves through the composition. If you look closely, you will find that it divides each square in half.

SB: These are compositional rules that serve as a guideline, but which are also playful.

BB: I always need to establish some kind of rule or idea. Otherwise, I wouldn’t know where to start; it would just be so accidental. I want there to be a certain truth I guess.

SB: There is a strong sense of compositional clarity, which becomes heightened by the restricted palette.

BB: The ground of these works is a light acrylic wash and I use black gouache on top. It is the contrast that establishes the lines of the two grids. The actual line drawing that sits on top is in white pencil. It appears more fragile and nuanced than the stark contrast of the underlying forms. You can exactly see where this line stops and starts. Meanwhile, the matte, deep black of the gouache is very sensuous. In fact, you can trace every fingerprint on it.

SB: Do you focus on one work at a time or do you explore these ideas simultaneously on several surfaces?

BB: One of the advantages drawings have is that you can work on them quickly and on one after the other. Generally, I will prepare several grounds before starting in charcoal on a group of drawings. If one doesn’t work out I will throw it out. However, in painting, I tend to work on at least eight to ten paintings at a time, because you have to wait for each layer to dry. During that stage of having to wait, I will turn a painting around. In general, painting is just a much slower process.

SB: Compared to your paintings, your drawings appear as somewhat reductive. In fact, whereas your paintings usually embrace a range of colors, your drawings are often black and white, monochrome, or limited to only a couple of hues. Would you say that your drawings are more simplified in order to focus on the structure of form?

BB: Yes. Drawing is really close to thinking, with the hand doing the thinking in a way. For centuries, painters have worked out compositional ideas or structural ideas in drawing first, before adding color, which is a richer medium.

SB: Do you think of color as adding an emotional component as well?

BB: No, it’s its own language, like drawing. I think of it as comparable to singing, one has to have a gift for it. I don’t like the idea of color adding an emotional aspect, because drawing can certainly be emotional on its own. Expressionist drawings, such as works by Kirchner for example, are very emotional. In contrast, some painting can be rather analytical, such as the work of Josef Albers. You can certainly play with cold and warm tones and use different colors to evoke certain emotions, but each individual will still experience them differently. Some people love black and others are scared of it. Color has to do with light and I think that different traditions of paintings have developed in countries, because of the light that you find there. The other day, I was looking at the paintings of Richard Diebenkorn, who was based in Los Angeles for much of his life. I remembered how disappointed I had been when I first discovered his work, because his colors seemed so washed out. I really only understood Diebenkorn’s palette when I went to Los Angeles myself and experienced how strong the light is there; it fades the colors. Meanwhile, New York has beautiful light and I think that’s part of the reason why there’s a great colorist tradition there. In Germany, light, except maybe for in the South, is not very good. I think that’s one of the reasons why Germany has a great tradition in drawing, printmaking and bookmaking. This certainly informed my decision to make primarily drawings in Berlin, which are reductive in color and line-based.

SB: In other words, your vision for your Berlin studio was partially informed by how you experience the larger cultural context?

BB: Yes, very much so, even though at first my decision was somewhat impulsive. I had been thinking about a drawing studio for a long time, simply because I can’t really focus on works on paper in my painting studio.

SB: Is this due to the fact that for you, both these mediums distract from each other?

BB: It’s a good question. I once spent a month at a residency in Upstate New York, called Yaddo, and I only worked on drawings there. When I came back I right away got myself a big tabletop, thinking that I would continue to work on my drawings. It just didn’t work. The paintings always took over. For me, both mediums require a different space, not just physically but also mentally.

SB: Though you were born, raised and studied in Germany, you have lived in the United States for a long time. Nevertheless, you have always kept a strong connection to Europe.

BB: I have always visited regularly, perhaps twice a year, as I still have friends and family in Germany. I also show my work regularly here. However, for about twenty years I was predominantly in the US. I would say that I have a certain split in me, allowing me a distance to both cultures.

SB: In a way, you never are truly at home. You sit between two chairs. In Germany, you are thought of as Americanized and in the US you are considered German.

BB: Exactly. It’s very strange. When I first came to Berlin, some Germans even thought that I was an American, who happened to speak German very well. That was an interesting experience.

SB: Above, you described your time in your Berlin studio as an opportunity to “open up” your work. How has this affected your paintings in New York? Do you bring back drawings made in Berlin to New York to develop them further or to even translate them into paintings?

BB: Yes, I do and it has really clarified my thought. In general, I think that the linear, the drawing element has become more obvious in my painting. Whereas before, different shapes were described and defined by borders, now they are rooted in line. Color and line are the two main oppositions in my compositions and I try to keep them both independent. I don’t use line as a mere outline, but as something that can establish its own structure and the same is true for color.

SB: Your work is abstract and yet, you have an independent, regular practice of landscape drawing.

BB: Yes. I have been doing landscape drawings since 1995, always working on site. In Berlin, these are often made while visiting the city’s many cemeteries. First, I went to different parks, but you usually encounter an atmosphere of entertainment there, which runs counter to the quality of timelessness and contemplation that I look for. I especially like a small World War II cemetery close to Südstern, which doesn’t have real graves, but just plates in the ground. These landscape drawings mark a separate group of work, which gives me a connection to the world. I certainly incorporate elements and ideas developed in these drawings into my abstract compositions, sometimes more directly and sometimes less.

SB: Did you already focus on abstraction while in art school?

BB: I went to art school in Munich and like most students tried different things. Basically, right after I finished in the mid-1980s, I came to New York. There, I switched from acrylic to oil, and began painting tree trunks at first. They were very large, telling of human intervention. After that I focused on architecture, figures, and landscapes. However, even as a figurative painter I was always leaning toward abstraction. Then, about eight years ago, my work became completely abstract. I had been resisting this step for a long time, but when I took it, there was a tremendous sense of liberation.

SB: Due to its history in Abstract Expressionism and the New York School, abstract art remains an important language in New York. In fact, I would argue that it is the more traditional one. You certainly are aware of the great abstract painters to an extent that it might feel overbearing; you have to measure up to that canon.

BB: Yes, exactly.

SB: Would you say that you work towards something that is already in your mind so that you are simply trying to find a concrete form for it, or do you develop visuals step-by-step and somewhat unconscious?

BB: I think it is different for drawing and painting. My painting is very process-oriented, so even though I start with certain ideas, it does develop over time. There is a kind of back and forth between trying to clarify the idea and then sort of messing it up again. Meanwhile, the drawings are more of a one-shot thing. While working on them, I can repeat the same idea again and again, inviting mistakes and slippages. The latter might even bring the work to somewhere completely new and unexpected. I don’t have a certain goal, but I do feel that I have developed this language in abstraction that has provided me with a solid plateau. On it, I can move around and just clarify things for myself.

SB: What makes a work successful and when do you determine that something is finished?

BB: Well, it’s a strange thing with finishing a painting. You never really know whether it is finished or not. Sometimes, I’m really happy with something; however, as time goes on, it gradually gets less interesting. It can also work the other way around in that something that I was unsure of and had turned around suddenly gets really exciting when reviewed on a later date. In general, there will be a sense of resolution and clarity in a painting if I determine that the composition is complete. However, this decision can take months.

SB: Does the same apply to drawings or is it easier to assess them?

BB: It is similar, but as the drawings are finished faster, the overall process of deciding whether they are finished or not, does not take as long either.

SB: Would you say that it’s easier for you to determine whether a drawing is successful than a painting?

BB: I don’t know, it is hard to judge your own work in terms of quality. I usually invite other artist friends to my studio when I have completed a new body of work. I like to listen to what they have to say in order to get an outside view. Sometimes, I will photograph the work in order to view it on the computer, which allows me a more remote look at it. Distance is important.

SB: Do you usually prefer to exhibit drawings and paintings together?

BB: Yes. I do, because it provides a look into the work process. Also, as my works are interconnected, I do believe that my drawings help the viewer to understand my paintings and vice versa. I also like to see that kind of presentation for other artists’ oeuvres.

SB: To view a painter’s drawings can feel like studying the bones of the composition. In addition, drawings are often very personal, allowing intimate insight into the thought that is at the root of observation. Think of Georges Seurat’s and Vincent Van Gogh’s black and white drawings, for example, which are incredibly expressive and yet a distilled concept from their luminous paintings. Drawings are often freer, uninhibited and perhaps because they relate to handwriting, are akin to taking notes without over-analyzing the moment.

BB: Absolutely. In drawing, there is very little disturbance between your thought and your hand. It’s wonderful. That’s also the reason why you can still read something intuitively, even when it is culturally unfamiliar, which in my case might be Chinese calligraphy, for example. Drawing is both intimate and private.

SB: What works by other artists are important to you?

BB: Well, you go through periods when you look more at certain artists or genres. For a while I looked specifically at Asian ink drawings. Matisse is important of course and Milton Avery and the Abstract Expressionists. Recently, there was an exquisite exhibition of Philip Guston’s grey paintings, which I thought was just tremendous [Philip Guston Painter, 1957 – 1967, Hauser & Wirth, New York, April 26 –July 29, 2016]. I also went to Ravenna to look at the mosaics and of course, the Agnes Martin retrospective, which I saw both at the Tate in London and the Guggenheim in New York [Agnes Martin, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, October 7, 2016 - January 11, 2017] was very important to me. I also read a lot. All of it enters your thought and your language. In the end, I think of myself as a formalist, to whom ideas, thoughts, and content make a painting. I don’t mean narrative content but abstraction is a language that exposes thoughts about the world just as much as figuration. In the end, that is what really excites me.

SB: Despite this formalism, would you still describe your work as a quest for self-exploration? Do you view your paintings and drawings as part of yourself or as being independent once they are completed?

BB: I think that my works are about the world and its various aspects as it is seen through me. I’m not interested in a personal or even diaristic position. My work is not about my habits, emotions, or about finding myself. However, it certainly embodies my point of view. Though I first paint for myself, I also paint for the world, for whoever might be interested in or connect with the work. Meanwhile, you’re part of a long line of artists; you’re in dialogue with living artists and those who came before you. This is of utmost importance, because like religion, all great art deals with the crucial questions of who we are as people.

“Fermaten und Oszillationen: Ein Gespräch zwischen DONNA HARKAVY und Bettina Blohm“ 2016

Donna Harkavy: Fangen wir vorne an. Kannst Du über Deine Vorgehensweise sprechen – wie Du ein Gemälde machst?

Bettina Blohm: Das erste, was ich im Atelier mache, sind Skizzen. Sie sind klein und einfach, ich zeichne sie in ein Skizzenbuch, mit einem HB Bleistift. Dort entwickle ich kompositorische Ideen für meine Ölbilder. Ich mache eine Zeichnung nach der anderen, Skizze um Skizze, und wenn ich etwas habe, das mich reizt, beginne ich mit einem Bild. Auch während das Bild entsteht, denke ich mit Zeichnungen weiter darüber nach. Oft fange ich eine ganze Gruppe von Arbeiten an, die mit ähnlichen Ideen zu tun haben. Ich verwende Ölfarbe und male in Schichten, und ich versuche, die Oberfläche offen zu halten. Gelegentlich geht es recht schnell, aber meistens dauert es etwa drei Monate, bis ein Bild fertig ist. Ich wische bestimmte Flächen wieder frei, ich übermale sie, und die Oberfläche wird interessanter, weil sie diesen Prozess widerspiegelt. Es gefällt mir, wenn die Entstehungsgeschichte zu spüren ist. Während eine Farbschicht trocknet – das dauert für gewöhnlich drei Tage – drehe ich das Bild zur Wand. Wenn ich es dann wieder anschaue, habe ich einen gewissen Abstand, und das hilft mir zu entscheiden, wie ich weitermache. Jedes Bild hat seine eigene Stimmung, seinen eigenen Charakter.

DH: Zeichnen ist ein wichtiger Teil Deines künstlerischen Prozesses. Du hast von Deinen Skizzen gesprochen. Was machst Du sonst noch für Zeichnungen?

BB: Einige sind Landschaftszeichnungen. Ich zeichne seit zwanzig Jahren in der Natur. Bei den Landschaftszeichnungen denke ich nicht ans Malen, ich halte im Grunde nur fest, was ich sehe. Da sie immer ein sehr kleines Format haben, 18 x 23 cm, entsteht ein direkter Flow vom Auge zur Hand. Eine andere Serie von Zeichnungen heisst Diagrams. Die Diagrams sind immer abstrakt. Sie entstehen in Berlin, wo ich vier Monate im Jahr lebe. In ihnen entwickle ich Ideen für Gemälde, speziell den Bildraum und die Struktur. Diagrams 2014 (S. 100) gehört zum Beispiel zu dem Ölbild Great Escape (S. 33).

DH: Bei den Gemälden sind Löschungen ein wesentlicher Bestandteil Deines Verfahrens. Gilt das gleichermaßen für Deine Zeichnungen?

BB: Bei den Landschaftszeichnungen radiere ich nicht. Wenn eine nicht funktioniert, werfe ich sie weg. Die Diagrams sind in Kohle auf Acrylgrund gezeichnet. Kohle ist ein sehr malerisches Zeichenmedium, und ich verwische mit der Hand. Dadurch bekommen die Zeichnungen manchmal diesen wunderbar dunklen Hintergrundton. Ich benutze die gezeichnete Linie und die halbverwischte Linie auch, um räumliche Abstufungen und den Eindruck von Ferne zu erzeugen.

DH: Vergleicht man Deine Zeichnungen mit den Gemälden, hat man den Eindruck, dass der Raum in den Zeichnungen oft dynamischer ist.

BB: Bei den Zeichnungen hat man nur eine Linie und das weiße Papier. Das Papier ist also bereits der Raum. Man muss ihn nicht erst konstruieren, wie bei einem Ölbild. Das ist das Wunderbare am Zeichnen, es ist dem Denken so nahe. In meinem Fall ist der Maßstab oft klein und er kommt aus der Hand, daher fließen die Denkprozesse direkt in die Zeichnung.

DH: Hat das Arbeiten in Berlin Deine Bilder beeinflusst?

BB: Ja, definitiv. Ich habe mir vor acht Jahren ein Atelier in Berlin eingerichtet und beschlossen, dort nur auf Papier zu arbeiten. Mit dem Ergebnis, dass die Linie in meiner Malerei an Bedeutung gewonnen hat. Durch das Hin und Her zwischen Malphasen und Zeichenphasen sind meine Bilder klarer geworden

DH: Wie entstehen die Titel Deiner Gemälde?

BB: Titel geben macht mir Spaß. In der Regel habe ich vorab keinen Titel. An irgendeinem Punkt innerhalb des Malprozesses übernimmt das Bild die Führung und ich folge ihm einfach. Dann kann der Titel plötzlich da sein. Es ist dieser Flow, der absolut wunderbar ist. Er kommt ganz von selbst, fast. Manchmal habe ich keinen Titel, manchmal kommt er im Nachhinein, ja sogar im Gespräch mit jemandem, der das Bild betrachtet. Es ist ganz unterschiedlich, wie ein Titel zustande kommt. Aber im Idealfall fügt er dem Gemälde eine weitere Schicht hinzu.

DH: Kommt es auch vor, dass der Titel das Gemälde leitet?

BB: Gelegentlich. Zum Beispiel, das Bild mit dem Titel Memory Palace (S. 19) beruht auf einem Raster. Bei diesem Bild hatte ich den Titel ziemlich schnell, schon beim Malen. Ich dachte an die uralte Technik, sich etwas ins Gedächtnis einzuprägen, bei der man sich eine Konstruktion vorstellt, meistens ein Bauwerk, und unterschiedliche Teile der Erinnerung in die Räume stellt.

DH: In Deinen neueren Bildern verwendest Du mehrmals ein Rasterformat. Wir kam es zu dieser Entwicklung?

BB: Zwischen 1995 und 2008 habe ich Landschaften gemalt. Bei einem Landschaftsraum landet man immer beim Horizont. Selbst wenn man ihn nicht verwendet oder negiert, ist er immer da. Bei den neueren Bildern wollte ich unbedingt die Senkrechte und die Waagrechte einbeziehen, und das Raster ist eine perfekte Kombination von beidem. Es ist auch ein gebauter Raum. Ein ausgesprochen urbaner Raum. Wenn ich bei mir aus dem Fenster schaue, sehe ich genau das. Und ein Raster ist nonhierarchisch, deshalb ist es eine perfekte moderne Struktur, und egalitär. Ich habe also alle diese Assoziationen im Kopf. Ich messe die Raster nicht unbedingt aus; oft sind sie mit der Hand gezogen und unregelmäßig, kippen ab oder biegen den Raum. Ich stelle sie auch mal auf eine Ecke, so dass sie eher rautenförmig sind. Das Raster schafft Ordnung, was mir zusagt. Du weißt ja, aus Chaos will man Ordnung herstellen, das ist ein ganz fundamentaler, menschlicher Impuls. Aber dann muss ich die Ordnung zerstören und brauche ein Gefühl von Freiheit; hier kommt das gestische Element dazu.

DH: Du hast im Hinblick auf Dein Werk oft über Chaos und Ordnung gesprochen. Kannst Du das näher erläutern?

BB: Es ist gut, Regeln festzulegen. Sie müssen aus der eigenen Malpraxis kommen; sie sollten nicht aufgesetzt sein, aber sie können hilfreich sein. Man kann nur innerhalb gewisser Grenzen frei sein, da Freiheit für sich genommen sinnlos ist. Die beiden Gegensätze, Ordnung und Chaos, Regeln und Freiheit, brauchen einander. Und ich gehe beim Malen hin und her – schaffe eine Ordnung und arbeite dann gegen sie an, breche aus ihr aus und kehre dann wieder zur Ordnung zurück.

DH: Wie Du gesagt hast, das Raster bietet Struktur und Ordnung.

BB: Ja, genau. Das Raster steht auch in Beziehung zum Format, dem Rechteck. Das Format des Bildes bestimmt den Raum. Als ich Landschaftsbilder malte, arbeitete ich mit einem extremen Querformat, weil ich auf die eine oder andere Art immer mit dem Horizont zu tun hatte. Das Rechteck ist ein klassisches Format der Malerei, und es ist ein angenehm offenes Format für das Raster. Mein derzeitiges Lieblingsformat, 172 x 213 cm, steht in Relation zu meiner Körpergröße und der Reichweite meines Arms, der Malprozess hängt also mit meinem Körper und der Armbewegung zusammen.

DH: Es wurde oft bemerkt, dass Deine Arbeit anfangs stark von Henri Matisse beeinflusst war, was die Verwendung breiter Flächen in kräftiger, flächiger Farbe angeht und die Partien, wo sich Formen an den Kanten berühren. Kannst Du etwas zu diesem Einfluss sagen, und zu anderen Künstlern, die Dein Werk geprägt haben?

BB: 1987 gab es eine Matisse-Ausstellung im Metropolitan Museum, Werke aus der Eremitage. Sie hat mich enorm beeindruckt. Damals malte ich Baumstämme in mehr oder weniger kubistischen Farben, bräunlich, bläulich. Ich ging nach Hause und malte den ganzen Baumstamm rot. Dann fing ich mit Farbstudien an. Anschließend eliminierte ich das Räumliche aus den Formen und führte mehr und mehr Farbe ein. Ja, Matisse war eine zentrale Figur. Auch Milton Avery und später Arthur Dove. Als ich Landschaften malte, waren Avery und Dove wichtig für mich, in punkto Farbe und was sie mit der Landschaft machten. Auch Doves emotionale und, soll ich sagen, spirituelle Beschäftigung mit Landschaft. Ich studierte, wie Matisse Formen voneinander abgrenzt. Wenn man mit flächiger Farbe arbeitet, sind die Kanten ganz wesentlich. Eine Zeitlang habe ich nur Kanten gemacht; alle Linien waren Kanten. Jetzt verwende ich die Linie natürlich eigenständiger.

DH: Gibt es zeitgenössische Künstler, deren Werk Du schätzt?

BB: Thomas Nozkowski, Jonathan Lasker und Mary Heilmann. Alle drei beharren auf einer persönlichen Sicht der Welt. Obwohl sie ihre Inspirationsquellen verbergen, weiß man, dass es etwas ist, was sie gesehen und erlebt haben, egal was. Und sowas interessiert mich. Für mich war es jahrelang die Landschaft, doch davor habe ich auch Architektur gemalt, irgendwann sogar Figuren, ich habe also über Jahre dieses Vokabular entwickelt, das ich verwenden kann, sogar in meiner heutigen Arbeit. Und deshalb mache ich weiter Landschaftszeichnungen, auch wenn ich nicht unbedingt male, was ich von den Zeichensessions nach Hause bringe. Es erhält den Kontakt zur Welt aufrecht. Es gibt mir Ideen. Ich schaue das Licht an – es gibt eine unendliche Vielfalt an Formen und Momenten in der Natur, die sich mit dem Licht ständig verändern. Als ich das erste Mal Gelegenheit hatte, in die Catskill Mountains zu fahren, habe ich so emotional reagiert, ich musste es einfach verwenden.

DH: Seit Beginn Deiner Tätigkeit oszilliert Dein Werk zwischen Landschaft und Abstraktion, und oft verharrt es, wie eine Fermate, dazwischen. Seit 2011 sind Strukturen zum vorherrschenden Motiv geworden. Was führte zu dieser Verschiebung von der Landschaft zu einem abstrakteren Vokabular?

BB: Ich empfand eine gewisse Begrenztheit oder Beschränktheit bei den Landschaften, weil ich wollte, dass das Gemälde autark ist und nichts mit Information zu tun hat, die erkannt werden muss. Ich glaube, ich bin gut im Abstrahieren, im Herausdestillieren des Wesentlichen, der Grundstrukturen von dem, was ich sehe, egal, was es ist. Aber ich sträubte mich dagegen, weil ich eine figurative Malerin sein wollte, obwohl das eigentlich gar nichts mehr bedeutet. Es gab also einen Punkt, an dem ich diesen Raum und das gegenständlichere Sujet aufgegeben habe. Es war eine Befreiung. Ich denke nicht unbedingt an Struktur. Es ist eine Art additiver Prozess; ich lege eine Form oder Geste an und wiederhole sie. Am Ende wird daraus eine Art Muster. Es besteht ein Zusammenhang zwischen Struktur und Abstraktion, und eine enge Verwandtschaft mit der Natur, den Formen und Gebilden, die wir in der Natur sehen. Und es geht um ein Gefühl von Ordnung.

DH: Deine jüngsten Bilder sind allem Anschein nach von Musik inspiriert. Sie sind so etwas wie ein visueller Punkt und Kontrapunkt musikalischer Rhythmen und multipler Motive, die aufeinander antworten und reagieren. Kannst Du etwas über Dein Verhältnis zur Musik sagen? Ist das etwas Neues für Dich?

BB: Im vergangenen Sommer (2015) machte mich Sabine Bergk auf Leonard Bernsteins Norton Lectures aufmerksam. Ich mochte sie sehr, weil er Verbindungen herstellte zwischen Musik und Dichtung, Kunst und sogar Linguistik. Er hielt sie 1973, also an einem kritischen Punkt, als der Moderne der Dampf ausgegangen war und die Postmoderne eingesetzt hatte, und die große Frage war, wie es weitergehen sollte. Ich fing an, mir Gedanken über Musik und Bernsteins Ideen zu machen, und so malte ich mehrere Bilder als Reaktion auf die Idee, musikalische Formen zu wiederholen und herumzuschieben. Eines meiner Bilder heisst sogar The Unanswered Question, so lautet der Titel seiner Lectures und einer Komposition von Charles Yves, die im Mittelpunkt der gesamten Vortragsreihe stand. Paul Klee, ein weiterer Künstler, der meine Arbeit beeinflusst hat, verstand viel von musikalischer Struktur und bringt das oft in seinen Bildraum ein.

DH: In diesen Bildern scheint es auch eine neue Art der Schichtung zu geben. In der Vergangenheit hast Du oft Schichten aufgebaut, sie jedoch unter breiten, flächigen Farbfeldern verborgen. Hier ist die Schichtung offensichtlicher. Du brichst die Oberfläche auf und legst unterschiedliche Arbeitsphasen frei.

BB: Ich wollte mich und den Betrachter fordern. In den neuen Bildern führe ich eine weitere Schicht ein, und indem ich mit dem Maßstab spiele, verschiebe ich ständig den Fokus. Formen werden vervielfältigt oder in unterschiedlicher Größe und Intensität wiederholt. Indem ich dünnen Farbauftrag mit pastoseren Stellen kontrastiere, kann ich ein Raumgefühl erzeugen, aber trotzdem flache Formen verwenden. Die Lasuren sind wie Fenster in den Raum. Es entsteht der Eindruck von Vor und Zurück, manchmal durch die übermalten Stellen und manchmal durch die Löschungen, das Wegwischen, auch das erzeugt Tiefenwirkung. Es ist, vom Raum her, anspruchsvoller.

DH: Der Eindruck, dass Du den Entstehungsprozess stärker offenlegst – glaubst Du, es hat etwas damit zu tun, dass Du älter wirst, selbstsicherer, mit dem Gefühl, nicht mehr so viel für Dich behalten zu müssen wie früher?

BB: Das wäre eine schöne Erklärung. Es mag unterschiedliche Gründe dafür geben. Es wird wieder mehr gemalt, daher bekomme ich mehr Input von Ausstellungen, von jungen Malern. Es gibt heute eine gewisse Lässigkeit in der Malerei, man will nicht so perfekt sein, sondern das Unvollkommene zeigen, die menschliche Hand. Und ich beherrsche meine Mittel besser und will sie stärker vorantreiben.

DH: Darum geht es, zum Teil, in Deiner Malerei: eine Form zu wählen und sie ans Limit zu treiben. Oder mit einem Typus, einer Form zu experimentieren und sie in verschiedene Richtungen zu treiben.

BB: Ja, ich hoffe zumindest, das ich das tue. Und alle Verhältnisse, alle Teile sollten sich aufeinander beziehen. Das ist sehr wichtig, dass das Bild ein Ganzes ist, dass es nicht einen Hintergrund und einen Vordergrund gibt, Figur und Grund, sondern dass sich alle Formen aufeinander beziehen und Eines das Andere bedingt, der Hintergrund bedingt die Figur und die Figur den Hintergrund. Das wäre mein Ideal.

DH: Gibt es einen abschließenden Gedanken, den Du hinzufügen möchtest?

BB: Jedes Gemälde hat im Kern eine Story, ich beginne nicht unbedingt mit ihr, aber ich suche danach. Darin besteht meine Neugier, welche Story steckt in dem neuen Bild, was wird es mir erzählen? Welche Realität wird es haben? Jedes Bild enthält eine Frage, und der Punkt ist, sie nicht zu beantworten, sondern die Frage zu verdeutlichen.

Donna Harkavy ist freie Kuratorin in New York.

Der Text ist ein Auszug aus einer Email-Korrespondenz vom 18. Januar 2016 und einem Live-Interview am 21. Januar 2016 in Bettina Blohms New Yorker Atelier.

Screen of Emotion, Landscape of the Mind

DIANE THODOS in conversation with Bettina Blohm

Portrait of the artist by BRUCE STRONG

www.artcritical.com, July 2004

Bettina Blohm's paintings are Haiku-like visual landscapes that distill emotion into abstract form. They reflect a love of Eastern art with its focus on intuitive states of mind. Blohm's paintings also engage with a Matisse inspired sense of color and an Abstract Expressionist scale, both of which come across especially within her compositional placement of gesture and shape. Enigmatic shapes or nature forms often seem to imply human presences. In earlier works where the human silhouette is depicted, more tensions arise which are emphasized by color contrasts and the formal placement of figures in relation to each other.

The following excerpts from an extended interview reveal the philosophy and approach she developed over 20 years as a painter and graphic artist. Her work forges together influences from Modernist and Asian art into a personal approach which is stands in opposition to prevailing postmodern and conceptual trends.

I am interested in your dedication to painting with historical roots in an aesthetic and Modernist tradition.

I work in the Modernist tradition. Someone once called me a third generation Abstract Expressionist. I believe the formal language is still relevant and can be built on. In the best Abstract Expressionist works there is a unity between the act of painting and their feeling and the world.

You clearly love the expansiveness of Abstract Expressionist scale and Matissean color.

Matisse is the greatest painter of the 20th century to me. Nobody else even comes close. Of course I love his color, but also his variety of formal solutions, his way of arresting shapes on canvas, and how each form is alive. His paintings are complex yet look simple.

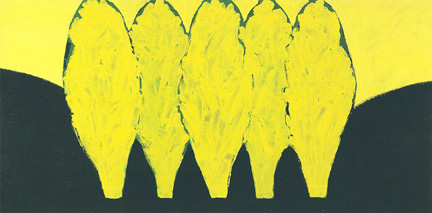

Bettina Blohm German Forest 1997

Bettina Blohm German Forest 1997

oil on canvasm, 48 x96 inches

Collection Pfalzgalerie Kaiserslautern, Germany

I tend to see a close analogy to your work in Milton Avery's landscapes where elements become compressed in simple abstract motifs.

I like Avery's color and the generosity in his later paintings. In those late works he achieves a beautiful synthesis between formal rigor and looseness and an exquisite poetic sense. In some paintings the motif becomes so compressed it is like a metaphor: a black and white bird hovering over a gray sea in Plunging Gull 1960 or the green horizon line which seems to contain the sea like a bathtub in Dunes and Sea 1960.

You have talked about your interest in Asian landscape painting and the abstract work of the Japanese American artist Miyoko Ito.

My first real encounter with Asian art was in 1992 in London at the exhibit of woodcuts by Hokusai at the Royal Academy. Certain images responded to my search for abstraction in figuration. Because Asian art was never that concerned with imitating nature the artists developed a greater individual freedom and expressiveness in their gesturers. I love the sense of poetry, of spareness, of essence, of humanity that I feel in these paintings. My ideas come from the visual world, or more specifically for the last 10 years from landscape, and that gives me something to push against. This is one of the pleasures I get from looking at Miyoko Ito's paintings. Her mature work is abstract and completely self contained yet it is obvious how hard she looked at the movement of water or the spatial construction of a landscape.

When you arrived in New York in 1984 you were making paintings of trees with a kind of Expressionist fervor. What did these early tree works signify to you?

I came to new York right after finishing art school in Munich. I chose the tree as a motif because I had a strong emotional connection with trees. I would walk around the city's parks and photograph different trees and then paint them in my studio. They were urban trees with chopped off branches which made them seem more human.

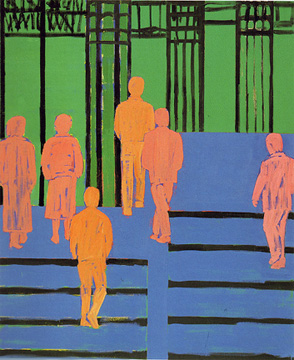

Bettina Blohm Where Are They Going 1992

oil on canvas, 82 x 68 inches

Collection Christian Friesecke

Human figure and silhouettes appear in your later paintings like Where Are They Going? from 1992. I cannot help feeling a sense of anonymity and distance in these figural works, with a rumble of emotional intensity just palpable below the surface. What was going through your mind?

At that time I hid my more emotional gestures under layers of flat paint and only at the borders between shapes could one see this undercurrent of turmoil. Formally it was a way to create depth. I wanted flat shapes but I also wanted to retain a sense of emotional urgency. Where Are They Going? was done at the time of the first Gulf war and the title reflects my feeling of hopelessness, the sense that everybody just followed mindlessly.

It seems nature and abstraction have given you a way for you to reflect on interior states of mind - a reflective space that at times balances between solitude and loneliness. Do you feel this too?

I always separate things. Every shape has a clear outline and there are borders; nowhere does one thing "bleed" into another. That may give a sense of isolation that you mention. I have a very strong sense of human loneliness and isolation: nature, however, offers me a sense of wholeness and connectedness.

I am struck by the difference between your works on paper and your paintings, especially because the paper works are more expressively stark and don't often use color.

I rarely use color because drawing, for me, is about mark making. Drawing is the most direct, honest or humble visual medium. You cannot lie with drawing. From a drawn line you can immediately see the temperament of the artist. This is one of the pleasures I have with Classical Chinese landscape painting: after many centuries and over vast cultural differences you can still see the individual artist at work.

How has growing up in Germany shaped your art? What are the things you see as distinctive about having a European background that are still with you living in New York?

Growing up in Europe I may have a stronger feeling for painting as a medium with a long history. But its a specific culture, in my case German. I only became conscious of it when I moved here. Being European I may have a stronger sense of the precarious nature of the world. Life is not black and white but has gray zones. I loved New York city as soon as I arrived. I loved the nervousness and chaos of the city. I also loved that women were treated as equal and one had the sense that it was still possible to add something to the history of art. Today I have a nice combination of both worlds. I work in New York and travel 2 - 3 times a year to Germany where I have had some success with shows.

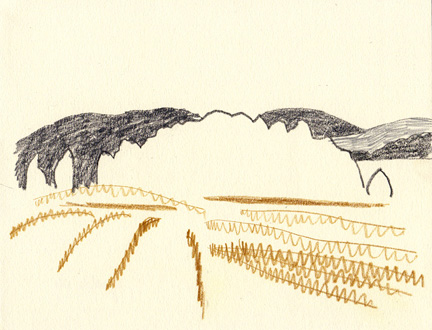

Bettina Blohm Untitled 2004

colored pencil on paper, 7 x 9 inches

Courtesy of the artist

You have been a committed painter for over 20 years with a consciousness of what is going on in the contemporary art world in New York over a long period of time. What is your view of present affairs?

As a friend of mine says: today artists are like racehorses. Again and again artists are destroyed through commercialization. It is a fundamental problem in the American art world and not new. Eugene O'Neill describes in his play Long Day's Journey into Night a gifted actor who got seduced by money and fame into playing the same part over and over.

And art education?

I believe art education has become too academic. Powerful emotions are at the basis of all art making. Today we do not have a compelling formal language as other times did and young artists have to find their way through a jungle of possibilities. The result is often an anxious obedience to the latest fashion.

What do you attribute this to?

Art movements have always been connected to political environments. There has been a feeling of apathy and cynicism, a feeling that nothing mattered but money that has been dominant in the art world and in the political system. The esthetic of an artist like John Currin is closely linked to the politics of George Bush; it is based on an all-pervasive contempt for people. If the political situation changes it may bring back some idealism and belief in art.

Diane Thodos is an artist and art critic who resides in Evanston, IL. She is a recipient of a Pollock Krasner Foundation Grant and is represented by the Paule Friedland and Alexandre Rivault Gallery in Paris.